The development of conceptual frameworks in assessing continuous quality improvement in healthcare organizations.

The proposal from AsIQuAS

Abstract

Quality Issue: To identify the organization’s strengths and weaknesses and provide suggestions and indications, improving healthcare quality is essential in health system management.

Initial Assessment and Procedure Choices: We explored previous studies’ perspectives and analyzed past academic and grey literature’s narrative, theoretical and conceptual works. We selected the contribution of some International Associations such as WHO, IOM, OECD and the Italian SIQuAS-VR, and other contributions such as “The Canadian Health Indicators Framework (CHIF)” and the one, by Di Stanislao Francesco, “La Qualità nell’assistenza Sanitaria e Sociosanitaria”, which was the initial driving force for drafting this paper.

Conclusions: The current challenge is to provide an innovative conceptual framework to facilitate the mechanism to assess the quality along different dimensions and achieve quality goals.

Keywords: Healthcare organizations; Quality improvement; Conceptual Frameworks, Quality dimensions; Healthcare Quality.

Authors

F. DI STANISLAO1, G. BANCHIERI2, C. E AMODDEO2, S. SCELSI2,R. CALDESI2, M. CAZZETTA2, S. GRENGHINI2, S. PRIORE2, S. SODO2, M. DAL MASO3, L. GOLDONI3, S. MARIANTONI3, M. RONCHETTI3, A. VANNUCCI3, U. WIENAND3, S. CARZANIGA4, G. CARACCI4, G. ACQUAVIVA5, A. CATALINI5, A. D’ALLEVA5, F. DIOTALLEVI5, A. MASIERO5, V. MONTAGNA5, A. PERILLI8, E. DE MATTIA6, C. ANGIOLETTI6, N. LONOCE1, A. PALINURO6, E. VALENTINI7, G. GRECO8, A.G. DE BELVIS2,6,7

1 Scientific Board ASIQuAS,

2 National Board of ASIQuAS,

3 Members of ASIQuAS,

4 AGENAS,

5 Institute of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine - Università Politecnica delle Marche,

6 Critical Pathways and Outcome Evaluation Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS,

7 Faculty of Economics, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore,

8 Department of Life Sciences and Public Health, Section of Hygiene, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

1 INTRODUCTION

People constantly look for quality products and services, particularly healthcare organizations.

Higher healthcare quality results in satisfaction for the patients, employees, and suppliers. If the quality of healthcare services improves, costs decrease, productivity increases, and better service would be available for patients, which enhances organizational performance, resulting in long-term working relationships for both employees and suppliers.

Specifically, Leebov and colleagues (2003) argue that quality in healthcare means “doing the right things right and making continuous improvements, obtaining the best possible clinical outcome, satisfying all customers, retaining talented staff and maintaining sound financial performance”1. In many countries, health stakeholders proposed different dimensions of quality to design conceptual frameworks and provide a system in assessing health services performances such as individual ability of practitioners, work teams and health services mechanisms, strategies or intervention 2. In this paper, we provide a brief overview of the evolution of the concept of quality improvement. Specifically, we define quality improvement as it exists today in healthcare organizations, provide an overview of quality improvement frameworks over the years, and finally, get to the examination of the proposal by AsIQuAS on its latest quality-improvement conceptual framework.

2 METHODS

This study, therefore, aims to provide a framework for healthcare service quality by exploring the perspectives of various previous studies. Analyzing the narrative, theoretical and conceptual works from past academic and grey literature was fundamental to developing this paper. Preliminary research was undertaken to investigate the evolution of the conceptual frameworks of quality in healthcare and the different health system efforts to implement them. Additional works were hand-searched and selected, focusing on relevant literature, critical policy and organizational documents.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Concept of quality improvement in healthcare

In the healthcare industry, Batalden and Davidoff 3 have defined quality improvement as a mixture of efforts by everyone involved, from clinicians to patients and systems of care to improve clinician knowledge and skills and enhance patient health. Quality improvement attempts to provide cost-effective, efficient, better quality healthcare for patients while improving processes within the healthcare industry. It is definable as a systematic continuous approach that aims to solve problems in healthcare, improve service provision and provide better outcomes for patients 4.

3.2 Development of quality improvement frameworks in healthcare

In several countries, healthcare organizations identified strategies for raising awareness of quality care. Further understanding the evolution of the conceptual frameworks requires identifying different health system efforts to provide the critical elements demanded and identifying indicators to measure various aspects of healthcare systems’ quality. Different conceptual frameworks for health system performance assessment have been proposed at an international and national level 5. We explored and selected the contribution of some associations in the continuous strategic planning process.

3.2.1 WHO four key elements

One of the first attempts to define quality in healthcare was made by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1983. WHO, instead of providing a descriptive definition of healthcare quality, decided to specify the following four “dimensions” (or “key elements”) of quality in health services: professional competence of healthcare workers; acceptable use of the resources; risk management and patient satisfaction 6.

3.2.2 IOM Six quality dimensions

Years later, in 1991, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified patient-centeredness as crucial to quality health care. The IOM proposed a framework that endorsed six key patient-centeredness dimensions to achieve significant gains in the quality of care provided and meet better patient needs and clinicians’ satisfaction 7.

| Safety | Avoiding injuries to patients from the care intended to help them. |

| Effectiveness | Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively). |

| Patient-centred model | Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively). |

| Timeliness | Reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care. |

| Efficiency | Avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy. |

| Equity | Providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status. |

3.2.3 The Canadian Health Indicators Framework (CHIF)

In June 2000, WHO conducted a comparison between 191 countries. The WHO based the study on their ability to achieve three goals: improving health, increasing responsiveness to meet the demands of the population, and ensuring that financial burdens were distributed equally. From this analysis, Canada ranks 30th in terms of overall health system performance. To improve its condition, Canada took a broad health performance approach to quantify health and healthcare progress investing in measuring and reporting on the performance of its health system. That has entailed developing and using a multi-dimensional ‘health indicators framework’. The Canadian Health Indicators Framework (CHIF) is divided into four primary levels: health status; non-medical determinants of health; health system performance; and community and health system characteristics. Every level includes different fields or dimensions. It provides data and information used to accelerate improvements in the healthcare system. Every dimension describes and assesses quality relative to users’ needs.

We can find the following four dimensions regarding the first level: health conditions, human functions, well-being and deaths. Within the “non-medical determinants of health” level, the dimensions, also four, are health behaviours, living and working conditions, personal resources, environmental factors. At the healthcare performance level, the six dimensions that we find are acceptability, accessibility, appropriateness, competence, continuity, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. Finally, the last level comprises three dimensions: community, health system and resources 8.

The conceptual framework combines the macro-categories and the fourteen dimensions and subsequently provides definitions for each mentioned dimension.

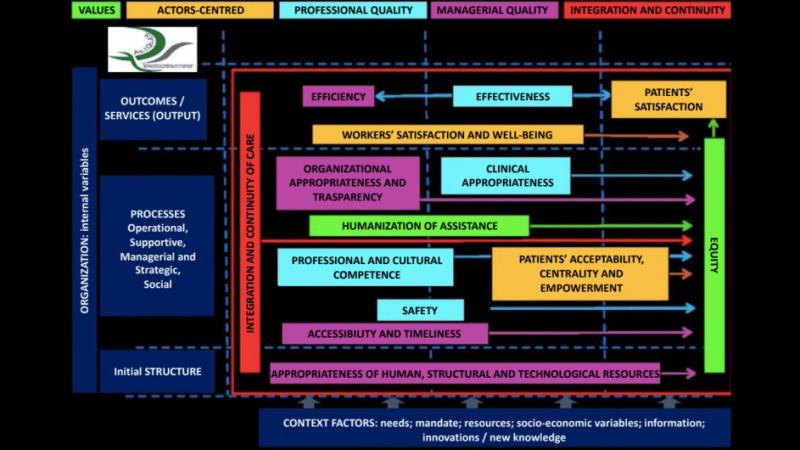

Value.

a) Equity: Health assistance does not change concerning the gender, race, ethnicity, geographical location or socio-economic status of the users/patients.

b) Humanization of assistance: It is essential to make the areas of assistance, the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways patient-oriented as much as possible, considering his/her physical, social and psychological aspects.

Actors-centred.

a) Workers’ satisfaction and well-being: Cultural elements, organizational processes and practices vivify a dynamic atmosphere and coexistence in a work context, promoting, maintaining and improving the quality of life and the level of physical, psychological and social well-being of the healthcare working force.

b) Patients’ satisfaction: It compares the expectations with which the user prepares to receive the type of service requested and the perceived performance.

c) Patients’ acceptability, centrality and empowerment: Providing healthcare services that are respectful and sensitive to individual patients’ preferences, needs and values. It must guide all clinical decisions.

Professional quality.

a) Effectiveness: Level of achievement of the health goals defined based on the individual’s health needs (or community) and prosecuted based on the scientific evidence available.

b) Clinical appropriateness: It is the correct use of an effective health intervention on the clinical conditions of patients who can benefit from it. It is based on evidence, clinical experience and good practices.

c) Professional and cultural competence: It is the proven ability to use personal, social and methodological knowledge and expertise in working or study environments and professional and personal development.

d) Safety: It is the ability to ensure the design and implementation of operating systems and processes to minimize the error probability, the potential risks and consequent possible patient harms. It is carried out by identifying, analyzing, and managing risks and possible patient accidents.

Managerial quality.

a) Efficiency: It is the ability to manage healthcare organizations, optimize resources and reduce/eliminate waste of equipment, supplies, ideas and energies.

b) Organizational appropriateness and transparency: Organizational appropriateness relates to providing a service in an adequate and congruent organizational context, considering the clinical complexity of the patient and the type of intervention/assistance to be provided. Organizational transparency is the easiness for users/stakeholders to find, acquire and understand the information required to receive and assess the quality of the service of interest.

c) Accessibility and Timeliness: Accessibility refers to providing healthcare services through operating settings that are easy to reach geographically, with appropriate skills and resources to health needs. Meanwhile, timeliness is the ability of the system to assist promptly with due regard for the expressed and recognized needs.

d) Appropriateness of human, structural and technological resources: It is the correspondence and the qualitative/quantitative updating of human, structural and technological resources in compliance with the patients’ actual needs, the national or regional legislation and the validated technological innovations.

Integration and continuity of care.

It refers to the provision of health assistance through the implementation of coordination and continuity of care and the interconnection of assistance and services according to people’s health needs and preferences within and between different institutions involved in the patients’ care 11.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Quality is difficult to define because of its subjective nature and intangible characteristics. Healthcare service quality is even more challenging to define and measure than other sectors. Distinct healthcare industry characteristics such as intangibility, heterogeneity, and simultaneity make defining and measuring quality difficult. The complex nature of healthcare practices, many participants with different interests in healthcare delivery and ethical considerations add to the difficulty. Although there are no uniform dimensions and indicators, all these frameworks have a common starting point – the conceptualization of the health system, defined more broadly or narrowly. The proposal from AsIQuAS is one of the most complete. It represents an additional reflection tool to identify the most critical quality dimensions. The conceptual framework provided by AsIQuAS could represent a milestone to define, at a later time, an innovative and complete monitoring system to measure the different dimensions of the quality.

Annexes N.1

References

1. Mosadeghrad AM. A conceptual framework for quality of care. Mater Sociomed. 2012;24(4):251-261. doi:10.5455/msm.2012.24.251-261

2. Di Stanislao F. Per una Sanità Pubblica dopo Covid 19 (Prima puntata). Quotidianosanita.it 04 Oct. 2021. https://www.quotidianosanita.it/stampa_articolo.php?articolo_id=98665

3. Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is "quality improvement" and how can it transform healthcare?. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):2-3. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

4. Backhouse A, Ogunlayi F. Quality improvement into practice BMJ 2020; 368 :m865 doi:10.1136/bmj.m865

5. Rohova M, Atanasova E, Dimova A, Koeva L, Koeva S. Health system performance assessment - an essential tool for health system improvement. Journal of IMAB - Annual Proceeding. 2017. DOI: 10.5272/jimab.2017234.1778

6. W.H.O (Working Group on the Principles of Quality Assurance; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe). . The Principles of quality assurance: report on a WHO meeting, Barcelona, 17-19 May 1983. Euro Report N. 94, 1985. (link)

7. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. PMID: 25057539.

8. Arah OA, Westert GP. Correlates of health and healthcare performance: applying the Canadian Health Indicators Framework at the provincial-territorial level. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:76. Published 2005 Dec 1. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-5-76

9. Onyebuchi A. Arah, Gert P. Westert, Jeremy Hurst, Niek S. Klazinga, A conceptual framework for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 18, Issue suppl_1, September 2006, Pages 5–13, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl024

10. Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J, Veillard J, Pichora EC, Januel JM, Arispe I, Kim SM, Klazinga NS; OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Expert Group. Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015 Apr;27(2):137-46. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv004. Epub 2015 Mar 10. PMID: 25758443.

11. Di Stanislao F. et Al. “La Qualità nell’assistenza sanitaria e Sociosanitaria”. Città di Castello-PG.COM. 2021.