Clinical Utility of a Relationship-Centered Health Care Model for the Management of Cardiologic Outpatients: a Real-World Experience in a Peripheral Rural Area

Abstract

Background

To evaluate the benefits provided by a relationship-centered health care model, focused on the optimization of both generalist-specialist and clinician-community relationships, implemented in 2009 in Mugello, a rural area in northeast Tuscany, for the management of cardiologic outpatients.

Methods

Crossing the database of the Health Regional Agency of Tuscany with hospital discharge records, diagnostic tests records and pharmaceutical prescriptions, we obtained demographic and clinical information about two populations: the patients resident in the Mugello area with a definite diagnosis of heart failure and/or ischemic heart disease obtained between January 2006 and December 2014 (exposed group), and the patients with the same diagnosis resident in the remaining regions of Tuscany with similar demographic and geographic characteristics (control group). The effects of the implementation of the model on clinical outcomes and health service utilization were assessed by the difference-in-differences estimation, comparing the changes across time in both the exposed and in the control group.

Results

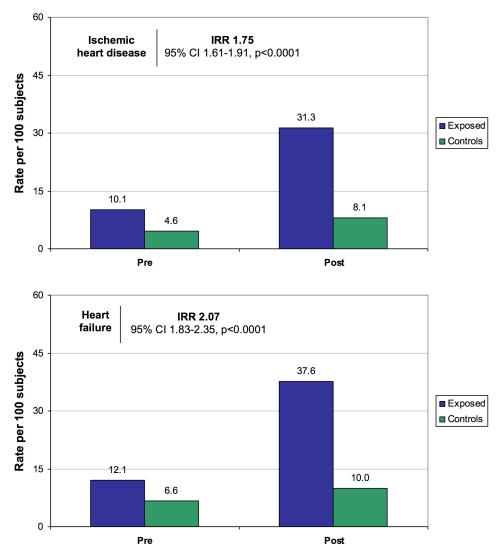

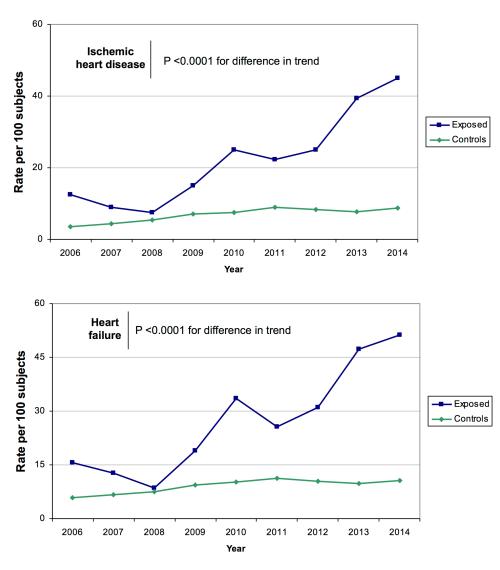

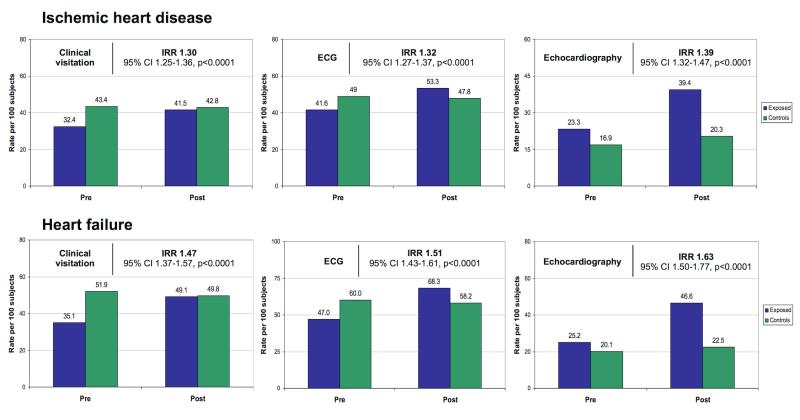

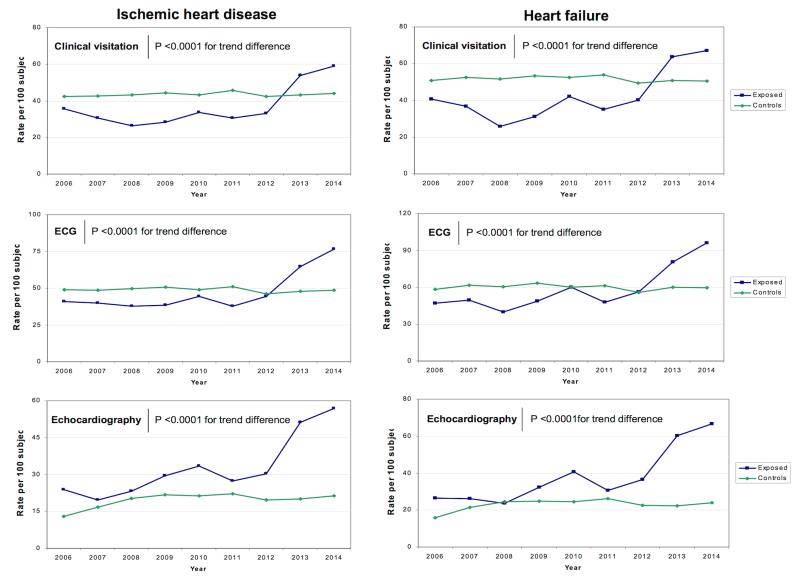

Compared to the controls, the exposed group showed a significantly higher increase in the rates of cardiologic consultations and of planned instrumental examinations performed within 3 months from the clinical consultation, and a larger decrease in the hospitalization rates related to ischemic heart disease and heart failure. In the cohort with ischemic heart disease, there was also a larger increase in the proportion of patients under beta-blocker treatment in the exposed group as compared to the controls.

Conclusions

Our study shows the utility of a healthcare model centred on relationships, and focused on optimizing all the interactions among the actors involved in the system, not just those between patient and physicians, thus going beyond the classical principles of patient-centeredness. Beside bringing favorable outcomes, this approch seems naturally tuned to and able to leverage on the nonlinear interactions characterizing complex systems such as the healthcare one.

Authors

Fabrizio Bandini1, Stefano Guidi1,2 , Piercarlo Ballo3, Silvia Forni4, Francesco Profili4, Mauro Vannucci5, Giovanni Banchi 6, Susanna Barbagli 6, Francesco Falcini 7, Antonietta Fumarulo MD, Domenico Rossi1, Fabrizio Cellerini1, Pasquale Petrone1, Margherita Padeletti1 , Chiara Chiriatti1, Serena Poli 1, Cristina Ciapetti 1 , Alfredo Zuppiroli4, Tania Chechi 3 , Andrea Vannucci 8 , Giancarlo Landini9, Paolo Marchese Morello10

1 Cardiology Unit Borgo San Lorenzo and Serristori, Local Healthcare Unit Tuscany Centre, Borgo San Lorenzo, Italy

2 Department of Social, Political and Communication Sciences, University of Siena, Italy

3 Cardiology Unit Santa Maria Annunziata, Local Healthcare Unit Tuscany Centre, Bagno a Ripoli, Italy

4 Quality and Equity Unit, Regional Health Agency of Tuscany, Florence, Italy

5 PA Bouturlin, Barberino di Mugello, Italy

6 AFT Mugello est

7AFT Mugello ovest

8 ASIQUAS

9 Department of Medicine and Medical Specialties, Local Healthcare Unit Tuscany Centre, Florence, Italy

10 Local Healthcare Unit Tuscany Centre, Florence, Italy

Background

It is known that the patient-physician relationship is a keystone of health care, providing the context where information is exchanged, diagnoses and plans are made, treatments are chosen, compliance is accomplished, and clinical outcomes are assessed [1]. A good relationship in terms of mutual respect, knowledge and trust improves the amount and quality of information about the disease that is transferred in both directions, allowing the physician to better understand patients’ clinical status, improving patient's comprehension of the disease, and favouring empathy, trust, decision-making capacity, and compliance [2]. On the other hand, recently there has been growing interest about the importance of adequate physicians’ interpersonal processes, particularly as regards the generalist-specialist relationships [3-5], and of good relationships between clinicians and the community [6]. This interest is based on the evidence that constructive interactions among different actors of the care delivery process are essential for a favourable patient outcome [7-8]. In this regard, the concept of relationship-centered care has been proposed as a constructive framework for a health care system where emphasis is given to personhoods, affects, emotions, reciprocal influence, and genuine trust at several levels [9]. These considerations raise the intriguing question of whether a health care model focused on the optimization of both generalist-specialist and clinician-community relationships could provide a benefit in terms of clinical outcome.

This study was set up to investigate the results of a real-world experience based on the implementation of a health care model aimed at optimizing these relationships for the management of cardiologic outpatients in a rural area.

Methods

Study population

The study population included all patients resident in the Mugello area, with a definite diagnosis of heart failure and/or ischemic heart disease obtained in the period between January 2006 and December 2014. Demographic and clinical variables were obtained using the database of the Health Regional Agency of Tuscany, which has been recently validated in a comparative study against medical records from primary care and national surveys [10]. To obtain a control group, firstly we identified, in the remaining regions of Tuscany, all areas with similar demographic and geographic characteristics. These included: presence of a town representing the local administrative center, proportion of mountainous districts, mean altitude (calculated as the average values of districts, weighted by the territorial area), mean age of residents, total population, density, and rurality (defined as the proportion of rural district in the area). Seven areas with characteristics similar to the Mugello area were identified (Lunigiana, Valle del Serchio, Alta Val di Cecina, Casentino, Val Tiberina, Val di Chiana Senese, Amiata Senese, Amiata Grossetana). All subjects with a similar diagnosis of heart failure and/or ischemic heart disease during the study period, resident in these similar regions of Tuscany, entered the control group. All the data used for the analyses are provided as additional files 1 (admission and beta blockers use) and 2 (consultations).

Key components of the model

The whole model was developed starting from a key concept, i.e. the central role of the relationships between generalists and specialists, and those between clinicians and the community, seen from both human and professional standpoints. The rationale of this approach was based on the hypothesis that optimizing the generalist-specialist relationships would have yielded a number of advantages, including a facilitated bidirectional information exchange, an improved appropriateness of requests for clinical and/or instrumental examinations, and a correct taking in charge of the patients within existing assistential continuity programs, ultimately leading to an overall improvement in patients’ practical management and resource optimization. On the other hand, optimizing the community-clinicians relationship could have lead to benefits in terms of patients’ empowerment, understanding of his/her condition, compliance to therapy and follow-up, and clinical outcome [1-2]. The practical implementation of the model was deployed in progressive steps. Firstly, the whole project was designed and agreed with all health care providers involved in the model, including the cardiologists of the community Hospital and those of the accredited private clinic, the GPs, and the direction of the Local Health Authority. All providers agreed on the need of strictly delimiting the intervention area by delineating a model where cardiology clinical consultations and instrumental examinations in the local facilities would have been provided only to the local resident population. Second, a number of interventions were planned to improve the relationships between different care providers. These included interventions aimed at 1) improving the hospital-primary care integration, 2) establishing an appropriate definition of clinical priority, 3) optimizing the diagnostic pathways, 4) favoring the contribution of cardiologic territorial facilities, and 5) enhancing patients’ empowerment.

Hospital-primary care integration. The first group of interventions aimed at strengthening territorial primary care medicine and favoring the communication between GPs and hospital specialists. The interventions included: a) meetings with GPs on the issue of appropriate use criteria for cardiology clinical consultations and instrumental examinations (performed three times per year since 2009), focused on the appropriate diagnostic pathways for main cardiologic clinical scenarios and aimed at reducing the rate of inappropriate requests from primary care; b) the activation of a direct phone service for hospital cardiology consultations, available each day from 8 AM to 8 PM, by which GPs could contact a hospital cardiologist to obtain immediate help and guidance for the clinical management of a specific patient; c) focused teaching courses (e.g., on ECG reading) to provide GPs with a first-level competence on specific topics. All these three interventions were planned under the hypothesis that an improvement in GPs’ cardiologic competence and a facilitated communication between them and hospital specialists – in the context of meetings, phone calls, or teaching courses – would have improved the reciprocal knowledge, trust and empathy between different physicians involved in the health care processes, favouring their relationships with potential benefits for the practical management of patients. In this regard, the activation of the phone service was planned and applied as a bidirectional tool, where the hospital cardiologist could contact the GP as well (e.g., during a hospital cardiology examination, to obtain additional information on patient’s history).

Appropriate definition of clinical priority. The second intervention aimed at clearly identifying priority criteria to appropriately define the correct timing and procedures for cardiology clinical consultations and/or instrumental examinations. The following three scenarios were then hypothesized, starting from the clinical evaluation performed by the GP: 1) need of urgent cardiologic consultation, in which the GP contacted the hospital cardiologist using the above mentioned phone service to plan the consultation within the next 36 hours (fast-track); 2) need of non-urgent, deferrable cardiologic consultation, to be scheduled using the Local Health Authority scheduling center; 3) need of single instrumental examination, again to be scheduled using the Local Health Authority scheduling center. Both deferrable consultations and instrumental examinations were schedulable either in the hospital cardiology service or in the accredited private clinic, but GP were encouraged to direct the patients to the accredited clinic for all first-level consultations, in order to save as much as possible the hospital resources for more complex or urgent cases, requiring more specialized investigations. On the other hand, the accredited clinic formally agreed to adopt the same consultation modalities as the hospital (see below), and, if needed, could refer patients to the hospital for further urgent tests and consultations using the same phone service used by GPs. Moreover, in the case of need of simple ECG, the patient could directly go each day, without an appointment, in one of the several territorial ambulatory offices, and get the ECG immediately read by a hospital cardiologist via a computerized service. The phone service was also available to help the GPs to choose the most appropriate scenario. Again, this intervention hinged on the hypothesis that favouring the relationship between GPs and hospital specialists for the definition of clinical priority would have been useful to improve the appropriateness of this clinical choice.

Optimizing the diagnostic pathways. This third group of interventions was designed to optimize the pathways of instrumental examinations for each patient, reducing the rate of inappropriate requests. To achieve this, it was decided that all urgent and non-urgent cardiologic hospital consultations (either performed at the hospital or in the accredited clinic) should have lasted at least 40 minutes, and would always have included a clinical visitation, an ECG, and a comprehensive or focused echocardiogram. Then, a set of basic additional instrumental examinations was defined, including carotid sinus massage, orthostatic hypotension test, exercise stress test, and 24-h ambulatory Holter ECG monitoring. It was then agreed that, in the context of the cardiologic consultation, the cardiologist would have decided whether some of these additional basic tests were appropriate. If so, these additional examinations would have been performed immediately or within 24 hours. At the end of this evaluation, the cardiologist – after sharing the results of the examinations with the GP and consulting with him – defined whether the patient 1) had his/her diagnostic pathway concluded with no need of further evaluations, 2) needed further clinical visitations and/or instrumental examinations, 3) needed a full taking in charge within assistential continuity programs because of the presence of a chronic illness, or 4) had to be hospitalized. To optimize and facilitate the practical issues related to this last case, a “continuity unit” formed by the hospital cardiologist and a dedicated nurse was also employed.

Cardiologic territorial facilities. In addition to the involvement of the accredited private clinic in the management of non-urgent cardiology consultations and instrumental examinations, various peripheral ambulatory offices were activated in the Mugello area, where external cardiology specialists could provide additional first-level cardiology consultations scheduled again using the Local Health Authority scheduling center.

Patients’ empowerment. A last group of interventions were planned to favour the population empowerment within the new health care model, with attention to its psychological, organizational, and social levels. These interventions included several scientific-didactic programs on local television stations aimed at educating the local population on specific topics and at explaining the characteristics and the functioning of the new health care model – as well as those of the general Tuscan healthcare system – promotional videos and brochures, focused teaching meeting in the schools with cardiologists and hospital nurses according to the “family and friend” method – a well known technique to favour scientific information dissemination by asking people to share what they learned with familiar and friends – and phone applications for both Android and iOS to facilitate the direct phone contact between people and the hospital services. The final objective of these interventions was not restricted to a better empowerment of the local populations, but also included – thanks to the information dissemination – an increased probability of achieving a good relationship between patients and physicians.

Endpoints

To assess the impact of the new health care model, the following endpoints were considered over time, by comparing average values in the years before implementation of the model (2006-2008) and those in the years after implementation of the model (2010-2014). As indexes of system ability to take in charge of patients, we assessed cardiologic consultation rates and the time intervals between cardiologic consultation and planned instrumental examinations (ECG, echocardiography, exercise stress test, and ambulatory ECG monitoring). As indexes of morbidity, we assessed the rates of hospitalization related to ischemic heart disease and heart failure. Lastly, as an index of adherence to clinical guidelines, we assessed the utilization rates of beta-blockers. Reliable information regarding these endpoints was also obtained using the administrative database of the Health Regional Agency of Tuscany, using unambiguous disease and examination ICD-9 codes. Information about hospitalization was obtained from hospital discharge records. Information about the use of beta-blockers was obtained using data provided by pharmaceutical prescriptions, while information about consultations and examinations was obtained from diagnostic tests records. A minimum of two prescriptions per year, performed 6 months apart, was considered to identify patients on beta-blocker treatment.

Statistical analysis

Differences in trends over time between patients exposed to the new model and the control group were assessed using the difference-in-differences method, a technique based on panel data regression that calculates the effect of an exposure variable on a given outcome by comparing the average change over time in the outcome variable observed in an exposed group to that observed in a control group. A p value <0.05 was considered for significance. The statistical software STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX), was used for all analyses.

Results

System ability to take in charge

Cardiologic consultation rates. There was a significantly higher increase in the rates of cardiologic consultations (i.e., clinical visitation plus ECG plus echocardiography performed in the same day) among exposed patients as compared with the controls, both in the group with ischemic heart disease and that with heart failure (Fig 1). The effect was also significant when assessed as a trend over the 8 years of the study period (Fig 2). These differences were consistently observed for each component of the cardiologic consultation (Figs 3-4).

References

1. Gómez G, Aillach E. Ways to improve the patient-physician relationship. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26: 453-7.

2. Dorr Goold S, Lipkin M Jr. The doctor-patient relationship: challenges, opportunities, and strategies. J Gen Intern Med .1999 Jan;14 Suppl 1: S26-33.

3. Curković M, Milošević M, Borovečki A, Mustajbegović J. Physicians' interpersonal relationships and professional standing seen through the eyes of the general public in 4. Croatia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8: 1135-42.

5. Piterman L, Koritsas S. Part II. General practitioner-specialist referral process. Intern Med J. 2005;35: 491-6.

6. Pearson SD. Principles of generalist-specialist relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14: S13-20.